Ermordeter Scheich am Samstag in Damaskus beerdigt

upg. Noch ist unklar, wer den Selbstmordanschlag vom Donnerstag auf Scheich Mohammad Said Ramadan al-Buti in Damaskus verübt hat. Für die unabhängige Plattform «Syria Comment» hat Islam-Spezialist Thomas Pierret von der Universität Edinburgh ein Portrait des Kirchenführers verfasst.

—

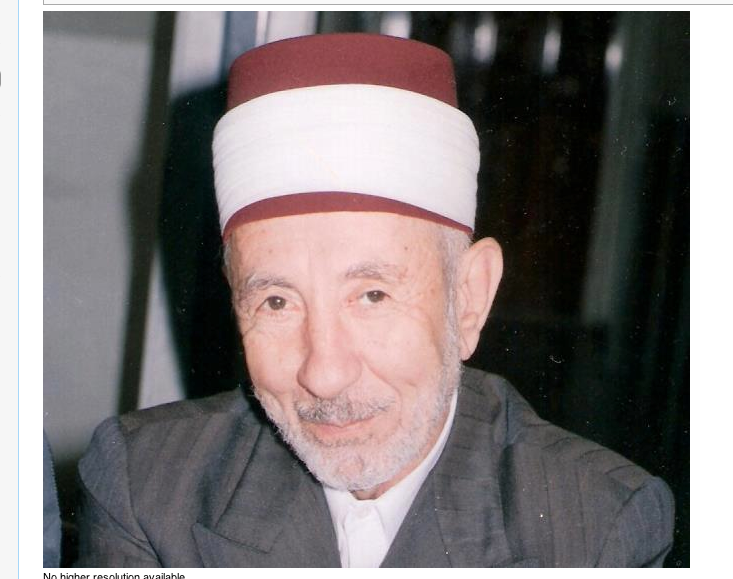

Syrian Regime Loses Last Credible Ally among the Sunni Ulama

With the assassination of Sheikh Muhammad Sa‘id Ramadan al-Buti (b. 1929), who was killed in Thursday’s bomb attack at the al-Iman mosque in Damascus, the Syrian regime lost its last credible ally among the Sunni religious elite. A Muslim scholar of world standing, al-Buti had conferred religious legitimacy on the Asad dynasty for more than three decades, with far more influence than discredited state creatures like Grand Mufti Ahmad Hassun.

The son of a Kurdish cleric who fled Kemalist repression and sought refuge in Damascus in the early 1930s, al-Buti earned a doctorate at al-Azhar before joining the staff of the faculty of sharia at the University of Damascus, of which he was dean from 1977 to 1983. In the meantime, he also became famous for polemical essays that were enormously popular among the religious-minded youth of the 1970s.

A staunch traditionalist, al-Buti was struggling on two fronts: on the one hand, he refuted western ideologies such as Marxism, nationalism and of course secularism; on the other hand, he relentlessly attacked the proponents of Islamic reform, from modernist Muhammad ‘Abduh to Salafi literalist Nasir al-Din al-Albani.

Al-Buti always remained a bitter enemy of non-traditionalist brands of Islam: a decade ago, he branded Islamic MP Muhammad Habash a »heretic” because he had claimed that the gates of paradise were open to Christians and Jews; a few years ago, al-Buti encouraged the regime to »cleanse” the country of Salafi zealots. His profound hostility to the central tenets of Baathist ideology did not prevent him from concluding an unlikely alliance with the Asad family.

Al-Buti made his first gestures of support for the regime during the 1979-82 insurgency: whereas most of his senior colleagues were either silent or supportive of the opposition, he vocally condemned the attacks carried out by Islamic militants. This stance was in line with his long-standing opposition to both military and political activism in the name of Islam, which had resulted in poor relations with the Muslim Brothers. Al-Buti’s quietist approach, which he fully expounded in 1993 in a book entitled Jihad in Islam, was in no way related to some secularist principles, but to the belief that Islam should be ‘the common element that unites’ all political forces rather than the preserve of one of them.

In exchange for helping the regime to defeat its Islamic opponents, al-Buti was endowed with informal leadership over Syrian Islam: although he did not occupy any prestigious position within the Ministry of Religious Endowments (awqaf) until his 2008 appointment as the preacher of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, he enjoyed a close relationship with Hafiz al-Asad, who used to grant him long personal meetings. Contrary to many pro-regime sheikhs, al-Buti did not use his political connections for personal enrichment. What he obtained in exchange for his loyalty was visibility through a weekly program on state television, as well the possibility to intercede in favour of some of his exiled colleagues who were willing to come back to the homeland. Therefore, criticisms of al-Buti’s pro-regime stance often went along with recognition that he had helped improve the situation of the religious elite after the fierce repression of the early 1980s.

Under Bashar al-Asad, al-Buti remained loyal to the regime in exchange for some concessions to the religious sector. In 2005, he branded the assassination of Rafiq al-Hariri as a US-Zionist conspiracy aimed at destroying Syria and Islam. Likewise, he described the execution of Saddam Hussein in 2007 as part of a US plan aimed at dividing Sunni and Shia Muslims, whom he called to unite, thereby repelling the opposition’s denunciation of the regime’s alliance with Iran. ‘Compensation’ for these declarations included a crackdown on women rights activism, more freedom for religious activities, a faculty of sharia in Aleppo, and the establishment of a short-lived League of the Ulama.

Following his appointment as the preacher of the Umayyad Mosque in 2008, al-Buti became increasingly influential within the Ministry of Religious Endowments by being entrusted with the supervision of an ambitious reform of higher Islamic education. On the eve of the 2011 revolution, however, relations with the authorities turned sour as a result of secularist measures such as a ban on face-veil (niqab) in schools and universities, as well as because of the broadcasting of a Ramadan series he deemed offensive to Islam.

In August 2010, al-Buti suggested that attacks on religion would entail painful retribution on the part of the Almighty: in a ‘vision’ he had in a dream, he said, he had seen a ‘devastating divine wrath filling the horizon’. A few months later, the Kurdish scholar first thought that this retribution had come under the form of the winter drought which for the third year, was hitting the country’s agriculture hard.

When demonstrations started in March 2011, al-Buti declared that this was the actual fulfillment of the godly vision he had had a few months earlier. Once again, the cleric gave credence to the regime’s narrative by speaking of a ‘Zionist conspiracy’. Although during the first weeks of the uprising al-Buti obtained further concessions like the closure of Damascus’ casino, the creation of a state-run Islamic satellite channel and his appointment as the head of a newly-created Union of the Ulama of Bilad al-Sham, his support for the regime gradually became unconditional and, above all, unlimited. A few days before his assassination, that is, two years into a conflict that had witnessed mass killing and destruction at the hands of the regime’s military, al-Buti was still encouraging the faithful to wage jihad in the ranks of the ‘heroic’ Syrian Arab Army, which he once compared to the Companions of the Prophet, in order to defeat the ‘global conspiracy’ against Syria.

Al-Buti, was the only respected scholar to express such vocal support for the regime after March 2011, the other religious sycophants being obscure, third-rank clerics, like Ahmad Sadiq, who was shot dead in Damascus a year ago. Therefore, regardless of who actually committed Thursday’s bomb attack (those who accuse the regime stress the fact that the attack took place in a heavily guarded neighbourhood, the al-Iman mosque being located a few meters away from the headquarters of the Ba‘th party; they also insist on the fact that bombing a Sunni mosque is an unprecedented pattern of operation on the part of Syrian insurgents (but it has been witnessed in Iraq), the tragic demise of al-Buti means that the regime has now ceased to enjoy any meaningful source of religious legitimacy among the Sunni clergy.

—

TEST: Mal sehen ob eine Änderungsmeldung kommt.

Themenbezogene Interessenbindung der Autorin/des Autors

Keine